Play Is Your Smartest Strategy: The Brain Science Behind How We Actually Learn

Think back to a test you studied hard for. You memorized everything the night before, aced the exam, and then... forgot it all a few weeks later.

Now think of something you learned by doing—maybe riding a bike, cooking your grandmother's recipe, or figuring out how to beat a level in a video game. You still remember it, don't you?

The difference isn't willpower or how hard you studied. The difference is how your brain is actually wired to learn. And it turns out, the most powerful learning tool has been hiding in plain sight: play.

This is the Learn pillar of the Propagating Play™ 4P System—understanding that the brain learns most effectively when play principles are at the center of how we approach education, skill-building, and growth.

Your Brain on Play vs. Your Brain on Pressure

Here's what neuroscience is discovering: when your brain engages in play, something fundamentally different happens compared to when you're stressed.

When you're stressed—say, studying for a test you're worried about—your body releases cortisol (the stress hormone). Research shows that chronic stress and test anxiety impair how your brain stores new information, particularly affecting the hippocampus, the brain region responsible for memory formation [2]. Your brain goes into self-protection mode rather than exploration mode.

But here's where it gets interesting: when you play, your brain releases dopamine and norepinephrine—neurochemicals that act like fertilizer for learning. Research indicates that dopamine enables reward to lead to long-term neural changes we want, facilitating the neuroplasticity (brain rewiring) that creates lasting memories [1]. The key difference? Play activates your brain's learning centers while keeping you calm and curious. Stress, particularly chronic anxiety, activates your brain's alarm system, which interferes with memory formation [4].

So if play creates the right brain chemistry for learning, the question becomes: what kind of play actually maximizes that learning?

The Magic Ingredient: Being Fully Engaged

You know that feeling when you're so absorbed in something that two hours disappear? You're not checking the clock. You're not thinking about whether you're doing it "right." You're just... in it.

Scientists call this "flow state," and it might be the most powerful condition your brain can be in for learning. Flow happens when three things line up: you have a clear goal, you get immediate feedback on how you're doing, and the challenge perfectly matches your skill level—hard enough to be interesting, but not so hard that you give up.

Research in educational settings shows that students who experience flow while learning demonstrate better information recall and problem-solving abilities [3]. Flow experiences also positively influence creativity and deep understanding.

Here's the beautiful part: play naturally creates all three of these conditions. A child building with blocks knows exactly what they're trying to create, they immediately see if it works (it either stands or falls), and they adjust the difficulty as they go. A scientist conducting an experiment has a question, gets instant results, and adapts the next step based on what they learned.

But here's the thing: flow isn't just a nice feeling. It's actually the container for something deeper to happen in the brain—something that happens through a very specific pattern.

The Try-Fail-Adjust Cycle That Changes Everything

Think about how kids actually learn through play. They try something. It doesn't work. They notice what went wrong. They try again differently. They succeed. Then they try something even harder.

That cycle—try, fail, adjust, succeed—is not just fun. It's the actual neurological pathway to real learning. And it only happens when you're in that flow state.

When you learn this way, you're not memorizing facts to regurgitate on a test. You're building flexible thinking. You're learning how to approach new problems with curiosity instead of panic.

Research on inquiry-based learning shows that when students learn through questions and exploration rather than passive instruction, they develop stronger problem-solving and creativity skills, and they take a more flexible approach to solving future problems [5, 6]. This is cognitive flexibility—the ability to think around a problem instead of getting stuck on one solution. And it's what the world actually needs from our kids (and from us as adults).

Now here's where it gets even more powerful: when you engage multiple senses during this try-fail-adjust process, your brain locks in the learning even more deeply.

Making Learning Stick Through Multiple Pathways

So we know play creates the right brain chemistry. We know it creates flow. We know it triggers the try-fail-adjust cycle that builds flexible thinking. But why do some play-based experiences create deeper learning than others?

The answer is that the most powerful learning experiences engage multiple senses and emotional systems at the same time.

Movement matters. When you're learning while moving—whether it's a child acting out the water cycle or conducting a hands-on science experiment—you activate multiple brain regions responsible for memory, attention, and emotional regulation. You're not just thinking about it; you're embodying it. The information gets encoded in your motor memory, not just your cognitive memory.

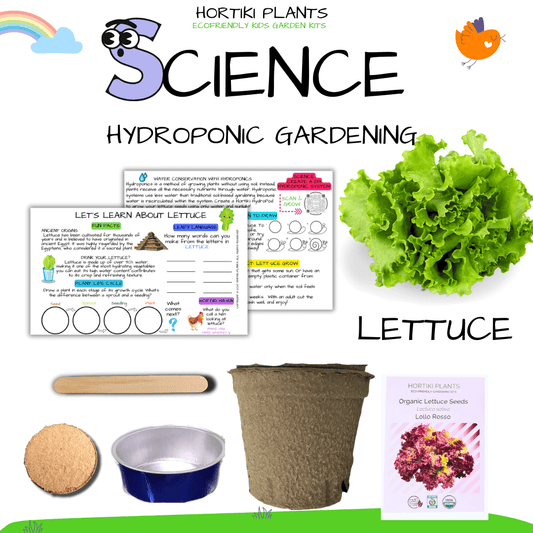

Emotion matters. Remember that dopamine we talked about? It's released through positive experiences. When learning is paired with joy, humor, or genuine interest, your brain prioritizes it and wants more of it. A child who learns plant biology by growing her own garden remembers it differently than a child who reads about it—not because she tried harder, but because her brain tagged it as important through emotional engagement.

Creativity matters. When you visualize a concept, draw it, build it, or express it in your own way, you're engaging both sides of your brain. Creative expression taps into the brain's plasticity in ways that passive reading simply cannot.

When movement, emotion, and creativity happen together within that try-fail-adjust cycle—that's when learning becomes unforgettable. That's when the brain rewiring actually sticks around for life.

What This Means for Your Child (or Your Classroom)

So what do we do with this?

It means that when your child wants to build an elaborate fort instead of doing homework, their brain might actually be doing something more important: building neural networks, experiencing flow, developing cognitive flexibility. It doesn't mean homework isn't valuable, but it means we need to rethink how learning happens.

It means that a science lesson where kids ask questions and explore answers creates deeper learning than a lesson where they memorize facts. It means that a math game where they problem-solve together builds different (and more lasting) skills than drilling flashcards. It means that when learning feels joyful and engaging, your brain is literally rewiring itself in ways that serve you for life.

You're Never Too Old to Learn This Way

Here's one more crucial thing: this isn't just for kids. Neuroplasticity continues throughout your entire life. Your adult brain is just as capable of being rewired through play, flow, and engagement as a child's brain. A CEO learning innovation strategy through team-based problem-solving activates the same learning mechanisms as a second-grader learning biology through gardening.

The neuroscience is identical. We never stop being wired to learn through play.

The Bottom Line

Emerging research increasingly suggests that play is one of our most powerful learning tools—creating conditions for deep understanding, creativity, and flexible thinking that many traditional approaches miss [4]. It's not about abandoning structure or standards. It's about recognizing that the human brain learns most effectively when it's engaged, curious, making mistakes in a safe space, and rewarded with the joy of figuring things out.

When we understand this—when we build learning around play instead of against it—we unlock something powerful. We stop asking kids to learn in spite of who they are. We start building learning experiences that align with how they're actually wired.

That's not just good teaching or parenting. That's neuroscience. And it's the Learn pillar of Propagating Play™ in action.

Play Works™ When You Make Space for Creativity and Flow

Ready to harness the power of play in your child's learning?

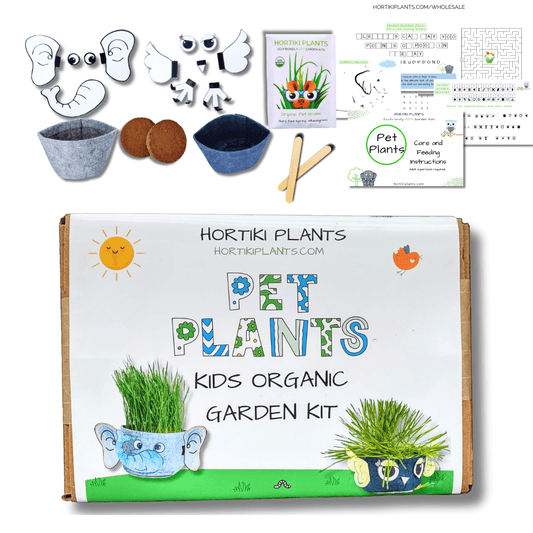

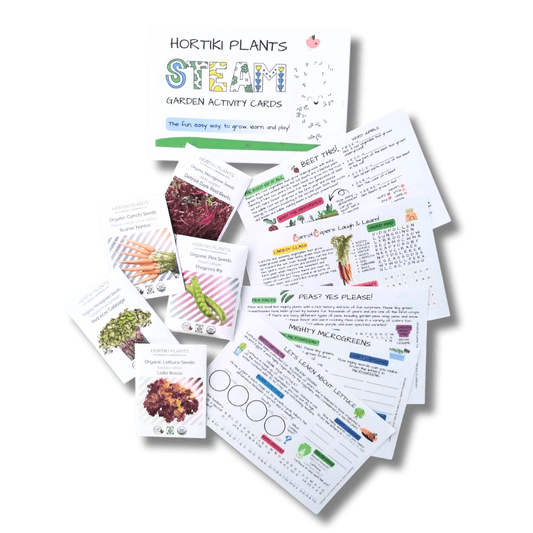

Hortiki's Kids Garden Kits turn learning into an adventure that the brain loves. We ditch passive instruction and ignite the power of inquiry-based discovery, challenging children to explore and create. Our resources leverage play as the highest form of cognitive training—not just for school, but for life.

Explore how our garden kits activate the try-fail-adjust cycle, create flow states, and build the neural pathways that lead to lasting learning and genuine joy in discovery.

Ready to transform how you approach learning in your own life? Our Team Courses and Workshops deliver the definitive science of play, giving you powerful tools—from movement to creativity to humor—that you can immediately use to optimize learning and peak performance. You gain the advantage of a mind operating at flow, unlocking joy and optimizing health through play.

A Note on the Research

The science of play and learning is still evolving, and researchers continue to explore the precise mechanisms across different contexts and ages. The findings cited here represent emerging scientific consensus from peer-reviewed research. As we learn more about how brains actually work, we're discovering that play may be one of our most powerful tools for building deeper understanding, developing creative thinking, strengthening memory retention, and fostering the cognitive flexibility our kids need to thrive.

References

[1] Duszkiewicz, A.J., et al. (2019). "Novelty and Dopaminergic Modulation of Memory Persistence." Trends in Neuroscience, 42(2), 102-114.

[2] Pagliaccio, D., et al. (2014). "Stress-system genes and the developmental trajectory of preterm infants." Psychoneuroendocrinology, 50, 131-143.

[3] Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1997). "Flow and education." Journal for Quality and Participation, 20(2), 32-37.

[4] Wang, S., & Aamodt, S. (2012). "Play, Stress, and the Learning Brain." Cerebrum, 12, 1-12.

[5] Spiro, R.J., et al. (1988). "Cognitive Flexibility Theory: Advanced Knowledge Acquisition in Ill-Structured Domains." Technical Report No. 441.

[6] Hmelo-Silver, C.E. (2004). "Problem-Based Learning: What and How Do Students Learn?" Educational Psychology Review, 16(3), 235-266.